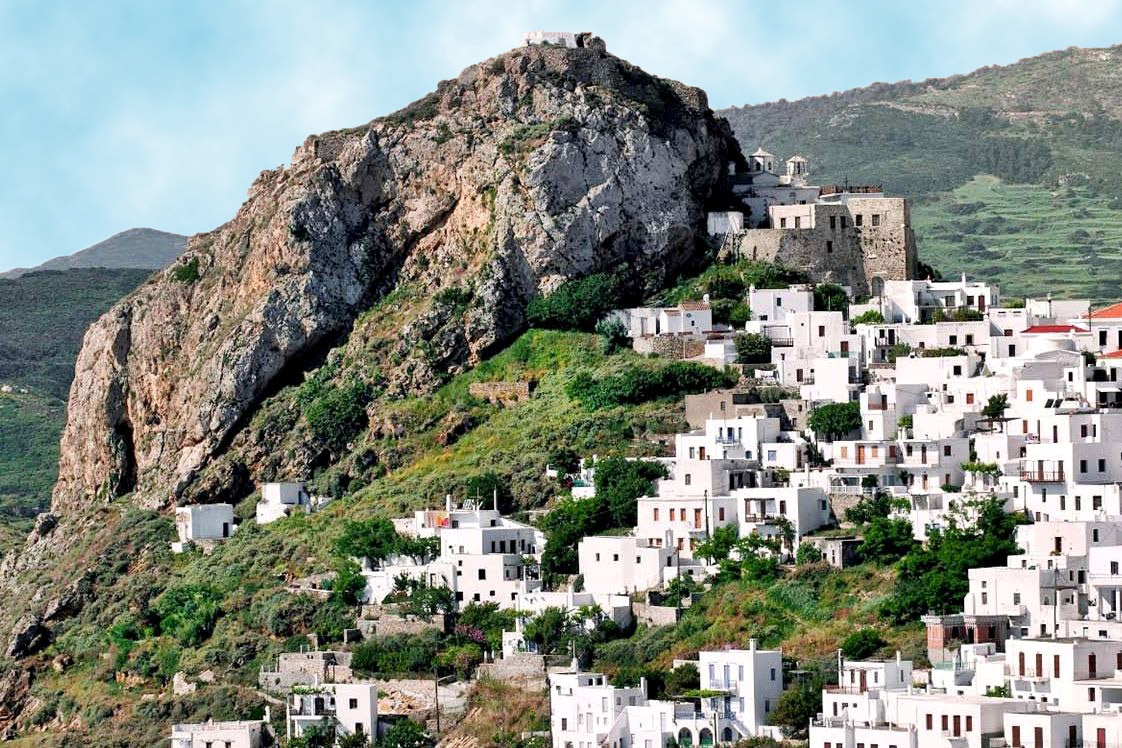

Chora, Skyros, Euboea,Central Greece

Castle of Skyros

| Location: |

| Chora, Skyros island |

| Region > Prefecture: |  |

| Central Greece Euboea | |

| Municipality > Town: | |

| City of Skyros • Chora | |

| Altitude: | |

| Elevation ≈ 179 m |

| Time of Construction | Origin | |

| In various periods | BYZANTINE |

|

| Castle Type | Condition | |

| Island Citadel |

Not Good

|

The castle of Skyros is at the top of a 179m steep rock overlooking the Chora of Skyros and the Aegean sea.

History

There was an acropolis on the rock since the age of mythology. Here was the palace of the notorious king Lycomedes who had killed the hero of Athens Theseus. Also, here is the place where Achilles was hiding dressed as a woman to avoid to join the Trojan war.

In 475 BC, the Athenian general Kimon captured Skyros which the Dolopes (a pre-Hellenic tribe) had made a base for their pirate raids. Kimon expelled the pirates and brought Athenian settlers to the island. In that campaign, he had found the bones and weapons of Theseus, which he brought to Athens, where the Theseion was founded to house them.

From the middle of the 9th century, Skyros belonged to the Thema of the Aegean Sea. Around the same time, it served as a place of exile.

In the 8th and 9th AD century, Skyros suffered from Saracen raids, culminating in the looting of the year 900, when the castle must have been captured.

A historical moment for Skyros and its castle was the foundation of the Episcopal Church of the Dormition around 895 AD. From the beginning and until the 19th century, the Diocese of Skyros was subordinate to the Metropolis of Athens.

The church, which was also the seat of the bishop, is located on top of the castle. It was for many years in ruins but has recently been partially restored.

Another milestone was the establishment of the Monastery of Agios Georgios on the lower side of the castle.

According to tradition, the monastery was founded by the monk Athanasios Athonitis (who founded also Megisti Lavra in Athos) with the support of Nikephoros Phokas after the reconquest of Crete in 963.

This story cannot be verified. It is more likely that a church dedicated to Saint George first appeared on the rock in the 11th century and developed into a famous and wealthy monastery. In 1289, by decision of the Patriarch of Constantinople Athanasios I, the monastery was granted to the Monastery of Agia Lavra in Athos as a dependency. This is the first historical reference to the monastery of the castle.

Saint George is the patron saint of Skyros. In fact, in Venetian documents and maps, Skyros is referred to as Isola San Giorgio (Island of Saint George).

At the beginning of the 13th century, after the Capture of Constantinople by the Frankish crusaders (1204) and in the chaotic situation that followed, various Latin adventurers (mainly Venetians) landed in the Aegean islands with the aim of seizing Byzantine lands and lay their hands on properties, following the example of Marco Sanoudo who had seized Naxos and other Cycladic islands.

Skyros was captured in 1207 by the Venetian Geremia Ghisi who also took Skiathos and Skopelos. (His brother Andrea Ghizi took Tinos and Mykonos.)

Skyros remained under the jurisdiction of the Ghisi family and Venice until 1277. In that year the Lombard knight Licario (from Euboea) captured Skyros and many other islands on behalf of the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII Paleologos.

In this way, the Ghizi period ended, and Skyros became Byzantine for two decades.

In 1299, Skyros was captured by the Venetian fleet. At the time, Venice and Byzantium were at war due to the massacre of the Venetians at Constantinople in 1296.

It is not clear what the status was on Skyros in the following decades, despite peace treaties between Venice-Constantinople in 1302 and 1310. Skyros was probably under (informal?) Venetian control. This theory is supported by the fact that in 1315 the presence of a Catholic bishop in Skyros, Ugulinus de Auximo, is recorded for the first and only time.

In 1354 the Duke of Naxos Ioannis I Sanudos (1341 - 1361) went to Skyros, after the defeat of the Venetians by the Genoese in the naval battle of Sapenza. It is not clear whether Sanoudos went to find refuge there or to occupy the island, but it seems that in the following period Skyros belonged to the Duchy of Naxos.

Later, in the 1370s, the 9th Duke of Naxos Niccolὸ III dalle Carceri (1371-1383), also known as Dallecarceris, made repairs and modifications to the castle’s fortifications, which since then took its final form.

In 1390, the Ottoman Turks built a fleet of 60 ships and Sultan Bayezid unleashed it in the Aegean. It was the first time that the Ottomans appeared dangerous also at sea. They succeeded in expelling the Venetians and occupying many Aegean islands, including Skyros.

In 1403 with the treaty of Gallipoli, when the Turks gave back some lands to Manuel II Palaiologos, Skyros was returned to Byzantium and for the next 50 years it remained a Byzantine possession. However, the island was almost deserted due to pirate raids that continued in the first half of the 15th century.

This period ended with the Fall of Byzantium in 1453.

In 1454 Venice, at the request of the inhabitants, annexed Skyros.

Throughout this turbulent period, the medieval and post-medieval years and later until the 19th century, the castle was always the refuge of the inhabitants, all of whom also had a second household inside the castle to use in difficult times.

In 1538 when – for the second consecutive year – the Turkish admiral-pirate Hayredin Barbarossa swept the Greek seas, Skyros was conquered and plundered. Venetian rule came to an end, but it seems that the Turks were in no hurry to impose their rule.

This is deducted from a document of the Monastery of Agios Georgios from 1556 regarding a case of encroachment on its properties, which is signed by the rector Carolo Grimaldi. It is possible that this Grimaldi was a Westerner in the service of the Turks, but probably what happened here was similar to what have happened in Naxos, where the Venetian dukes remained as vassals of the Turks until 1564 despite the devastation of 1537.

Eventually, Turkish rule began for Skyros after 1570, when, together with 33 Aegean islands it was granted by Sultan Murat III (1574-1595) to Kapudan Pasha (Chief-Admiral). Islanders had to pay taxes, but otherwise had relative freedom and privileges.

During the Tourkokratia, there was some construction activity on the castle: Many houses were built (mainly as second homes) and some repairs were made to the wall. The monastery of Agios Georgios was completely reconstructed in the period 1599-1602, by the monk Sosipatros, according to an inscription to the right of the bell tower, and gradually expanded to occupy almost all the space on the lower level of the castle.

Unlike other islands, the Skyrians did not excel in naval activities as they were more involved in agriculture. Embroidery and woodcarving were also developed in a very particular way, which later developed into know-how for the famous Skyrian furniture.

Many foreign travelers visited Skyros from time to time, the first being the Florentine Cristoforo Buondelmonti who traveled to the Aegean and Crete and wrote the Liber insularum Archipelagi in 1420. Other well-known foreigners followed, such as the Italians Bordone, Porcacchi and Rosaccioo (16th century ) and the Dutchman Olfert Dapper (17th century). Travelers describe a place with few and poor inhabitants but with excellent wine and good cheeses.

The Jesuit J.Sauger traveling between 1680 and 1687 writes that the Turkish power in Skyros is limited to a cadi who is a pawn the games of the local elders. He also tells outrageous stories of magic and superstition concerning the miraculous icon of Saint George.

The French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort visited the island in 1702 and recorded that there was a single settlement, under the rock of the castle, today’s Chora. The population was 300 families.

In 1806 the English colonel William Leake reports that most of the houses in the castle are abandoned except for the Episcopal Church. But the rich of Skyros still kept some houses in the castle, which at that time were used as warehouses to keep their valuables. He also mentions that the 500 families of the island paid an annual tax of 20 pouches to the commander of the Ottoman fleet.

The Turkish rule was interrupted for a few years after 1652 when the Venetian fleet captured the island during the 5th Venetian-Turkish War (1645-1669). It was interrupted again in the Orlof events (1770-1774), when the Russian fleet had ousted the Turks from the Aegean. A Russian squadron was anchoring at that time in Skyros.

During the years of the Greek Revolution, Skyros suffered from armed gangs settled on the island which under the pretext of the revolutionary fight against the Turks, demanded that the islanders feed them and pay them. It was a period of anarchy and fear. In order to find a solution, in 1826 a Greek minister came to Skyros and placed a guard on the castle with police duties. Eventually the island was freed from Turks and other robber gangs, but it suffered a lot in those years, while for a long time the inhabitants of Chora lived permanently in the castle.

Adter the end of those events, the castle has been abandoned. In 1837, the last bishop of Skyros, Grigorios, who was the last permanent resident of the castle, passed away.

In 1834, as part of the (anti-)monastic policy of the Bavarian regency of king Otto, the Monastery of Agios Georgios was abolished. However, it was reopened in 1848, after protests by the people of Skyros.

Until the middle of the 20th century, on the upper level of the castle, many old houses existed, which were demolished. In the upper part remained the large cistern, three small churches and the ruins of the bishopric.

Access to the castle and the monastery for many years was not possible due to restoration work after the serious damages in the earthquake of 2001. Recently, in 2019, after the end of the works, visits to the castle were allowed again, while to the monastery from 1215.

Structure, Fortification & Buildings

The castle is not preserved in good condition. One of the reasons is that the Venetians did not make major renovations here (nor did the Turks later) as in other Aegean castles that are relatively better preserved.

The three sides of the rock are steep and almost vertical. Only one, the northwest, is approachable and descends smoothly to the lower hills where the Chora is built.

The medieval castle consists of two levels. The main castle which is on the plateau of the top of the hill and a second level on a smaller plateau, lower, on the north-west side of the hill, where the entrance to the castle was and where the monastery of Agios Georgios is located.

But there is also a third level with the ancient fortification of Skyros. The ancient walls were much lower, they surrounded the rock and their original perimeter included a large part of today's Chora. Some remains of this wall are still visible. More visible are 4 ancient towers.

More specifically:

1. Upper level – Top of the castle

The summit plateau, on the upper level, has an area of 10,000 sq.m. with a fortification perimeter of approximately 410 meters. The walls are preserved almost all around the perimeter, although not in good condition. The enclosure zigzags a lot because it follows the contour of the edge of the cliff. The height of the walls today (but possibly always) does not exceed much the ground level of the interior.

In the masonry, 3 different phases are observed (one on top of the other): the first consists of square stones and bricks with lime mortar; it belongs to the Byzantine period. The second consists of smaller stones with a lot of binding mortar and external plaster; it belongs to the Venetian period of the 14th century. The third phase is almost dry stone with rough stones; for plastering the local dark mortar (melangi) is used; it involves rough repairs and additions made from the 16th century onwards.

In addition, the eastern side of the upper castle rests partly on an ancient wall on which rests a Roman one. Traces of the ancient fortification can also be seen on the south side. There, in some places, the medieval wall has been built a couple of meters further inside the ancient one, apparently because the rock had given way due to landslides.

The brownstone of the rock has been used in masonry throughout the ages, meaning that the ancient builders quarried the rock to build its fortification. In the medieval phases, second-hand building material has been used too (taken from the ancient wall), while a few spolia have also been embedded.

At the highest point, a building is preserved, without entrance and windows, called “dark prison” (photo 8). It is the most distinctive building in the castle with dimensions of 15.0✖9.5m, maximum height of 7m. and thick walls, 1.6 to 2m thick. Inside, it has two vaulted spaces with plaster on the walls and a slope on the floor for water drainage. Its name implies that it was a prison, but it is definitely a cistern. Having said that, the unusual position on the highest point of the rock, as well as the massive and strong structure, indicate that the building was originally a tower which underwent modifications when the upper floors collapsed, and after some time (perhaps in the 16th century), was used as a cistern.

There are two other cisterns on the castle. There is one embedded into the western wall measuring 8✖6m. Almost destroyed today. It appears to have been the ground floor of a tower (also seen in Coronelli's plan). The third cistern has dimensions 9.7✖4.0m. and it is on the eastern slope, outside the walls.

On the northern edge of the summit fortification, the foundations of a building with thick walls can be seen, which was probably the northern tower depicted in Coronneli's plan (17th century, see above the LAYOUT). A small bastion measuring 5✖5m is preserved on the south side, which can also be seen on the 17th century plan.

The upper castle had its own gate on its west side, where the path from the monastery led. This gate was protected by a tower. The gate and its tower no longer survive. They collapsed (by an earthquake?) relatively recently. We have black and white photographs of them. The current paved road from the monastery to the upper castle leads to another point, not the initial entrance, because the point of the destroyed gate is blocked by rubble.

In the upper castle, the remains of the bishopric are preserved. It was the residence of the Bishop and a temple dedicated to the Dormition of the Virgin (photos 9, 10). The Bishopric was used until 1837. In 1841 it was destroyed by an earthquake. Recently, restoration work is being carried out. In the upper castle there are also 3 newer churches. Two of them are in the center, next to the "prison", and the third a little further and lower, on the south side. The small churches are all that remains of the post-Byzantine settlement that was razed in the 20th century.

2. Lower level of the castle

The second and lower level of the castle is a small triangular plateau with an area of less than 1000 sq.m, which today is almost entirely occupied by the complex of the Monastery of Saint George. At the northern end of the plateau was the main gate of the castle (“Panoporta” or “Iron Gate”), which was protected by a strong fortification. This plateau was also defended by a wall on its western side, which went up to the secondary gate in the upper castle. The western lower wall no longer exists (because of the expansion of the monastery), but the fortification of the gate incorporating a tower and newer spaces, stretched on a chekered line about 30 meters long, survives to a considerable height (photos 5, 10).

Above the gate there is an inscription: “By Sevastos Georgios of Chaitelis”. The title Sevastos indicates that Chaitelis was a Byzantine official of the 11th or 12th century.

Further above, a relief with the symbol of Venice, the Lion, has been embedded (photo 7).

The fortification of Panoporta gives the impression today that it is the facade of the monastery of Agios Georgios. But originally the monastery was much smaller and the fortification was built independently of it.

The lower part of the gate fortification has Byzantine masonry, while the upper part has additions and repairs made in more recent years, perhaps from the 17th century onwards. In the masonry we see large stones with binding mortar and bricks up to the second floor while in the third (which is the post-medieval addition) we see a wall of small stones, without bricks and with large windows (something forbidden in medieval towers). Apart from the post-Byzantine interventions, in its original form the gate tower must have been at least one floor higher, as can be seen from older depictions. In Gouffler's engraving (1776, see ARTWORK above) the fortified gate complex looks much more imposing than the castle itself!

Passing the Panoporta a paved path leads to a fork. To the left it goes to the monastery and straight on to the upper castle.

The catholicon of the Monastery is elevated 6 meters from the gate. It retains the form it took after the radical renovation of monk Sosipatros at the beginning of the 17th century. The iconostasis and frescoes are from 1788.

3. Ancient Fortification

Lower than the castle and around Chora there are the remains of the ancient fortification, from the Classical Period, from which 4 semicircular towers remain. And they have names: The two smallest, “Agios Nikolaos” and “Agia Paraskevi” are located on the eastern side (photo 10) and the “Pergos” with a diameter of 8 meters on the western side between the houses of Chora. A piece of the ancient wall 5 meters long survives perpendicular to this western tower, and another larger piece lies between the towers on the eastern slope.

The most impressive of the towers is the “Paliopyrgos” at the northern end of Chora (photo 11) with a diameter of 19 meters.

| First entry in Kastrologos: | October 2012 | Last update of info and text: | May 2023 | Last addition of photo/video: | May 2023 |

Sources

- Αρχιμανδρίτης Καλλίστρατος-Κωνσταντίνος Οικονόμου, Ι. Μ. Αγίου Γεωργίου Σκύρου - Μετόχιο της Μεγίστης Λαύρας (13ος-19ος αι.), Διδακτορική Διατριβή. Αθήνα 2006

- Michalis Karambinis, The Island of Skyros from Late Roman to Early Modern Times. An Archaeological Survey, Leifen University Press, 2015

|

|

| Access |

|---|

| Approach to the monument: |

| A few minutes walk from Chora of Skyros |

| Entrance: |

| ? |

| Other castles around |

|---|